Osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease (DJD) is a challenge that horse vets and owners are faced with commonly, particularly as performance horses grow older. It can be a challenging condition to manage, as no one solution is suitable for every joint, every horse, every discipline or every owner.

Older joints degenerate

DJD is a normal aging process in all species, including equines. It can be aggravated by poor conformation, heavy workload, concussion from hard surfaces and poor shoeing. Equine DJD can also occur as a result of injuries such as knee chips in racehorses so can also be diagnosed in young or middle-aged horses.

Healthy cartilage glides, joint fluid lubricates and cushions.

A healthy joint has smooth cartilage covering the ends of bones contained within a ‘balloon’ of synovial fluid. The lining of the joint is called the synovial membrane. The synovial membrane produces synovial fluid which lubricates the cartilage surfaces to allow frictionless movement of the joint. It also cushions and protects the cartilage and underlying bone.

The cumulative effects of months or years of microtrauma, compression or abrasions to the cartilage surface cause the release of inflammatory chemicals into the joint. As inflammation and disease progress, the cartilage surface becomes further damaged, bony spurs or osteophytes form on the joint surfaces and fibrosis develops around the joint, restricting movement and causing stiffness. Eventually these changes can lead to lameness that can affect performance.

Signs of DJD vary

The degree of lameness a horse develops does not always show the true extent or severity of osteoarthritic changes within a joint. Some changes occur very gradually, allowing the horse to compensate. Acute injuries or rapidly developing DJD may cause joints to feel hot. Reduced range of motion or pain on joint flexion is a common sign, as is swelling or effusion of the joints.

We see DJD in differing joints depending on the use of the horse; as a generalisation coffin joint and foot problems are more common in older dressage horses, hacks or eventers. Western horses more frequently present with hind limb lameness due to hock or stifle arthritis, polocrosse and stock horses are commonly seen for pastern issues and racehorses tend to be affected in the fetlock and knee joints.

Diagnosis of DJD

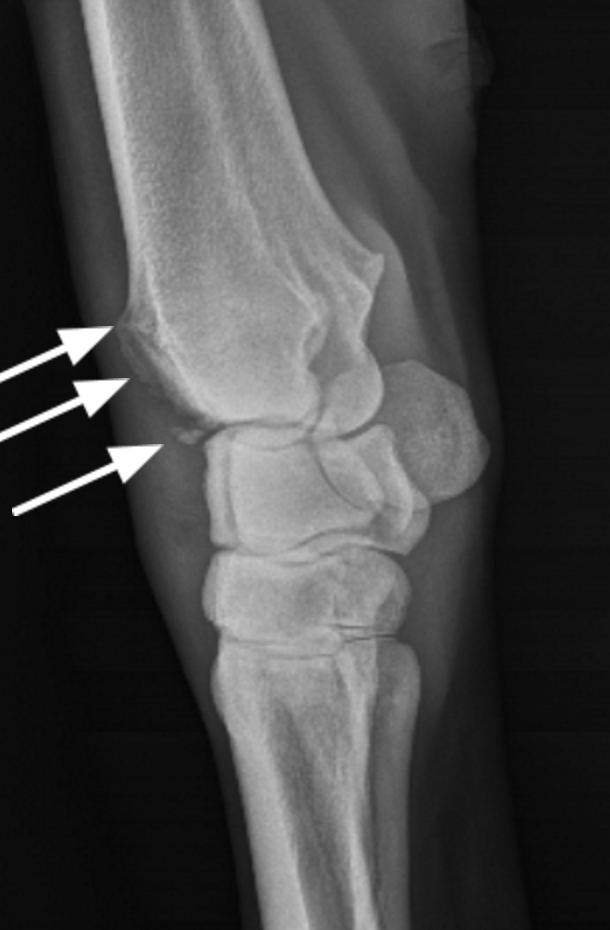

Radiography (X-rays), ultrasound of ligaments and cartilage, MRI, CT, and arthroscopy are all techniques that are used to evaluate joint disease. X-rays are most commonly available to vets but don’t always identify some subtle conditions. Vets look for joint space narrowing, osteophytes and small holes within bone. With time, fragments and chips may occur.

Arthroscopy can be invaluable for diagnosing and managing tricky joint problems in the horse. Most horse joints are relatively large, allowing good access for instruments and making surgery an effective treatment for certain situations e.g. removing bone chips. MRI and CT are not widely available in Australia and mostly restricted to university or large referral hospitals.

Medical Treatment of DJD

The aim of medical treatment of a horse with DJD is to provide protection to the cartilage surface, improve the quality of the joint fluid and reduce inflammation in order to halt or improve clinical signs, such as lameness. There are a number of therapies which are either prescribed by vets, or sell as ‘over the counter’ preparations.

- Corticorticosteroids (‘steroids’) are usually injected directly into the joint, often in combination with hyaluronate. They are potent anti-inflammatory drugs so often improve lameness; however they can be detrimental with long-term use as some studies suggest they cause accelerated cartilage damage. Racing Australia and the FEI have strict rules regarding their use for horses competing under these organisations.

Fig 1 Intra-articular injection of Cortisone/ Hyaluronate into a fetlock joint. This is done under sterile conditions, but the hair coat is not always shaved, depending on owner/trainers preference. This horse has visible swollen joint pouches due to degenerative joint disease.

- Anti-inflammatory drugs such as Phenylbutazone (‘bute’), flunixin or metacam are effective in giving symptomatic relief to animals with pain, heat or swelling. They can be administered in a variety of ways. There are also rules regarding the use of these drugs for many disciplines.

- Hyaluronate helps to improve the quality of the joint fluid, giving better viscosity and improved lubrication to an arthritic joint. It can be given as an intravenous injection or injected directly into a joint, often in combination with corticosteroids.

Fig 2 Advanced degenerative joint disease in this racehorses’ knee showing new bone growth or osteophytes and chip fractures (arrows).

- 4CYTE™ Equine is an oral supplement derived from plant oils, sweet lip mussel, abalone and marine cartilage. Studies have proven its ability to reduce intra-articular inflammation and many riders endorse its’ positive effects. The benefits are also preventative, so it can be administered to horses at risk of DJD as well as those already affected.

- Glucosamine and Chondroitin sulphate are oral supplements that are commonly available with many different names and formulations. These supplements are meant to help with cartilage regeneration and may be anti-inflammatory. Clinical response often varies.

- Pentosan polysulphate is an intramuscular injection that has proven anti-inflammatory and chondro-protective properties. Treatment programs with Pentosan can be highly individualised but many horses respond well.

- Tiludronate (Tildren®) is a drug that targets excessive bone remodelling, helping with mineralisation and bone density. It can be helpful for hock arthritis and navicular disease.

- Regenerative therapies including IRAP, PRP and stem cells are a relatively new area for the management of DJD and too big a topic to cover here. These therapies are helping many horses that suffer with DJD and in our clinic often form part of a multi-therapy approach to management of osteoarthritis.

Figure 3 Arthroscopic surgery. Dr Steve Rayner guides the arthroscope into a fetlock joint. The adjacent screen shows the interior of the joint.

The above information is Australian advice and meant as a guide only. There is no magic bullet! We recommend you speak to your vet and make informed decisions based on their advice.

(this article first appeared in July 2016 Horse Deals magazine- Australia’s highest selling horse magazine.)